Chicago’s complicated relationship with alcohol is older than classic Old Style signs, Al Capone, or local option. The city was barely twenty-one before alcohol began permanently changing its cultural and political structure. On April 21st, 1855, one thousand German immigrants, joined by some Irish neighbors, marched on city hall in protest of liquor laws which turned their beer against them.

Antagonized by a nativist (anti-immigrant) mayor and a rapidly expanding police force, the demonstration quickly turned violent. Chicago’s Lager Beer Riot transformed the downtown intersection of Clark and Randolph into a battleground over immigrant rights, local politics, and the moral fate of the city. German immigrants fought not just for beer, but for their place in the community.

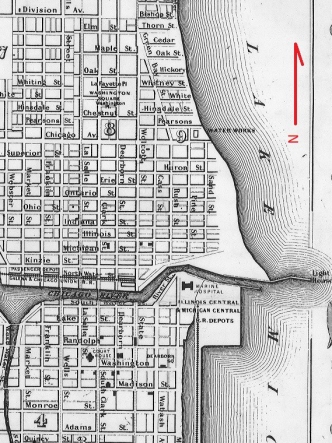

German Chicagoans typically lived on the North Side (or Nord Seite), across the Chicago River from downtown. One visitor wrote, “every other male engaged in selling beer, and the rest of the men, women, and children consume it.” Beer was more than a beverage—it was an integral cultural handhold for immigrants settling into a new home. For those making or selling it, beer represented their economic livelihood. Local German brewers like John Huck and Conrad Seipp eagerly provided lager beer for saloons, whose daily shipment could run dry by three in the afternoon. Outdoor beer gardens filled each Sunday with music and dancing as families celebrated the end of another work week.

This was an affront to citizens who opposed the ballooning immigrant population, alcohol consumption, or both. Nativists and temperance reformers accused the stereotypical “beer-be-muddled” German or whiskey-tippling Irishman of inflicting crime, corruption, and immorality on the city. They joined forces under the banner of the American, or Know-Nothing Party and, with the help of the Chicago Tribune, swept the city elections in March 1855. Running on a militantly pro-temperance platform, the Know-Nothings won six of ten seats on the city council and all major elected offices.

Levi Boone, the newly elected mayor, wasted no time targeting the city’s alcohol retailers, which were overwhelmingly immigrant-owned. The city resurrected a defunct Sunday ban on liquor sales and raised the cost of a liquor license from $50 to $300, while the license’s effective term shortened to three months. To enforce the law, Boone recruited men “of strong physical powers, sober, regular habits, and known moral integrity” (read: no immigrants need apply) to expand the police force. Hundreds were arrested.

Boone believed he was preparing for the inevitable—a statewide ban on alcohol had recently passed in the Illinois General Assembly but required a general referendum to become law. That was scheduled for June. Confident prohibition would pass, Boone claimed he wanted to stem the flow of alcohol in Chicago until then, and ween the city off its drinking habit.

But immigrants were the real target. Each Sunday the police closely watched German-owned beer halls to prevent illegal sales, while nativist haunts were given a wink and a nod. Valentin Blatz, a German saloon-owner, responded by closing his curtains and stacking empty beer glasses against his windows, dampening sound so passing police could not hear the ruckus inside. His customers, meanwhile, entered through a secret door in the adjacent physician’s office.

German neighborhoods reacted quickly, accusing Boone of stripping their rights and marginalizing them based on their ethnicity. The backlash started peacefully—Germans held public meetings and submitted numerous petitions. The city rejected them all.

As tensions mounted and the city retained its staunch temperance position, immigrant saloons owners (many of whom had dutifully paid the old license fee) began to operate without a license. More arrests followed, the city jail filled with violators, and the German community raised funds for their legal defense. To prevent a deadlock, the courts agreed to let the verdict of one test case stand for all license violations.

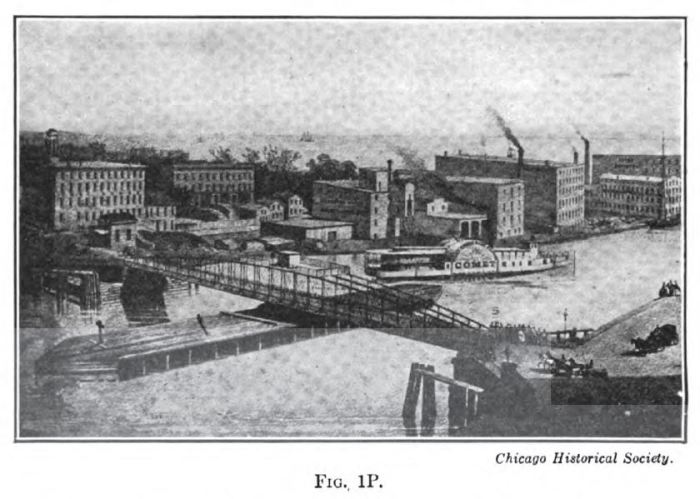

The First North Side War (as it was later called) began on the morning of April 21, when the court was scheduled to deliver its opinion. Hundreds of immigrants gathered on the North Side and marched down Clark Street, determined to send a clear message and, if necessary, free their imprisoned comrades. They filled the courtroom, then the vestibule, then the outer hallways. Soon the police were summoned.

As the mob was herded outside, an untimely shove from the police captain started a brawl in the street. Alderman Stephan La Rue, who represented a German ward, climbed atop a wagon amidst the melee. No one knows whether he was calling for peace or egging the mob on, for all he managed to say was “My friends!” before police yanked him down and arrested him.

Though outnumbered, the police scattered the rioters, who retreated across the river. Mayor Boone swore in one hundred additional police officers and called for militia reinforcements, convinced the mob would return. He was right.

That afternoon, the reformed mob was spotted marching down Clark Street again, armed with revolvers, muskets, and various cudgels. To buy time, Boone ordered the swing bridge at Clark Street opened, trapping the rioters across the river until he was ready for them.

When the mob returned to Clark and Randolph, a wall of police was waiting for them. Someone yelled, “Pick out the Stars!” and both sides opened fire. One German was killed, and numerous others injured. Two officers were shot but survived. According to the Tribune, the mob retreated into the area’s numerous lager beer halls, which the police subsequently raided and arrested anyone with a weapon.

Determined to enforce order, Boone declared martial law. Militia units and even cannon were deployed around the courthouse square, poised to fire on the mob should they return. They never did.

Boone’s harsh tactics fractured his political coalition and inflamed the Nord Seite. Without support, his policies faded. The license law barely lasted the summer. That June, the prohibition referendum failed in Chicago and subsequently the state, thanks to unprecedented voter participation in the heavily German northern wards.

No one arrested during the riot ever faced punishment, and the Know Nothings left office as quickly as they had come. Soon after the riot, several German beer halls opened on Randolph Street, overlooking the courthouse.

Following the riot, Germans became more active in Chicago’s political and cultural life than ever before, and today the city embraces its German roots. Daley Plaza hosts the famed Christkindlmarket every December, mere steps from Clark and Randolph (I try to attend every year, and have yet to see artillery). Yet the culmination of Chicago’s diverse and amicable populace cannot belie the negotiations, and sometimes conflict, that forge communities. Differing perspectives and values compel us to clarify exactly what matters. For Chicago’s immigrant Germans in 1855, their desire for a prosperous cultural space within their new home frothed inside their beer glasses. They considered it worth fighting for.

I love Maifest too. It’s my favorite street fest in Chicago by far. It makes me happy to hear Chicagoans progressing into celebrating the different cultures around the city. Good food and liquor is great at bringing people together. A lesson we could definitely learn today too.

LikeLike

When was this published?

LikeLike

Looks like I first posted this on May 4, 2017.

LikeLike

kool

LikeLike